In this post am going to explain (in highly simplified terms) two very important statistical concepts – the sampling distribution and central limit theorem.

The sampling distribution is the distribution of means collected from random samples taken from a population. So, for example, if i have a population of life expectancies around the globe. I draw five different samples from it. For each sample set I calculate the mean. The collection of those means would make up my sample distribution. Generally, the mean of the sample distribution will equal the mean of the population, and the standard deviation of the sample distribution will equal the standard deviation of the population.

The central limit theorem states that the sampling distribution of the mean of any independent,random variable will be normal or nearly normal, if the sample size is large enough. How large is “large enough”? The answer depends on two factors.

- The shape of the underlying population. The more closely the original population resembles a normal distribution, the fewer sample points will be required. (from stattrek.com).

The main use of the sampling distribution is to verify the accuracy of many statistics and population they were based upon.

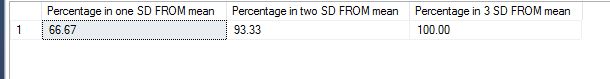

Let me try demonstrating this with an example in TSQL. I am going to use [Production].[WorkOrder] table from Adventureworks2016. To begin with, am going to test if this data is actually a normal distribution in of itself. I use the Empirical rule test I have described here for this. Running the code for the test, I get values that tell me that this data is very skewed and hence not a normal distribution.

DECLARE @sdev numeric(18,2), @mean numeric(18, 2), @sigma1 numeric(18, 2), @sigma2 numeric(18, 2), @sigma3 numeric(18, 2)

DECLARE @totalcount numeric(18, 2)

SELECT @sdev = SQRT(var(orderqty)) FROM [Production].[WorkOrder]

SELECT @mean = sum(orderqty)/count(*) FROM [Production].[WorkOrder]

SELECT @totalcount = count(*) FROM [Production].[WorkOrder] where orderqty > 0

SELECT @sigma1 = (count(*)/@totalcount)*100 FROM [Production].[WorkOrder] WHERE orderqty >= @mean-@sdev and orderqty<= @mean+@sdev

SELECT @sigma2 = (count(*)/@totalcount)*100 FROM [Production].[WorkOrder] WHERE orderqty >= @mean-(2*@sdev) and orderqty<= @mean+(2*@sdev)

SELECT @sigma3 = (count(*)/@totalcount)*100 FROM [Production].[WorkOrder] WHERE orderqty >= @mean-(3*@sdev) and orderqty<= @mean+(3*@sdev)

SELECT @sigma1 AS 'Percentage in one SD FROM mean', @sigma2 AS 'Percentage in two SD FROM mean', @sigma3 as 'Percentage in 3 SD FROM mean

In order for the data to be a normal distribution – the following conditions have to be met –

68% of data falls within the first standard deviation from the mean.

95% fall within two standard deviations.

99.7% fall within three standard deviations.

The results we get from above query suggest to us that the raw data does not quite align with these rules and hence is not a normal distribution.

Now, let us create a sampling distribution from this. To do this we need to pull a few random samples of the data. I used the query suggested here to pull random samples from tables. I pull 30 samples in all and put them into tables.

SELECT * INTO [Production].[WorkOrderSample20]

FROM [Production].[WorkOrder]

WHERE (ABS(CAST((BINARY_CHECKSUM(*) * RAND()) as int)) % 100) < 20

I run this query 30 times and change the name of the table the results go into, so am now left with 30 tables with random samples of data from main table.

Now, I have to calculate the mean of each sample, pool it all together and then re run the test for normal distribution to see what we get. I do all of that below.

DECLARE @samplingdist TABLE (samplemean INT)

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample1]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample2]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample3]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample4]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample5]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample6]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample7]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample8]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample9]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample10]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample11]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample12]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample13]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample14]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample15]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample16]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample17]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample18]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample19]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample20]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample21]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample22]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample23]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample24]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample25]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample26]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample27]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample28]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample29]

INSERT INTO @samplingdist (samplemean)

select sum(orderqty)/count(*) from [Production].[WorkOrderSample30]

DECLARE @sdev numeric(18,2), @mean numeric(18, 2), @sigma1 numeric(18, 2), @sigma2 numeric(18, 2), @sigma3 numeric(18, 2)

DECLARE @totalcount numeric(18, 2)

SELECT @sdev = SQRT(var(samplemean)) FROM @samplingdist

SELECT @mean = sum(samplemean)/count(*) FROM @samplingdist

SELECT @totalcount = count(*) FROM @samplingdist

SELECT @sigma1 = (count(*)/@totalcount)*100 FROM @samplingdist WHERE samplemean >= @mean-@sdev and samplemean<= @mean+@sdev

SELECT @sigma2 = (count(*)/@totalcount)*100 FROM @samplingdist WHERE samplemean >= @mean-(2*@sdev) and samplemean<= @mean+(2*@sdev)

SELECT @sigma3 = (count(*)/@totalcount)*100 FROM @samplingdist WHERE samplemean >= @mean-(3*@sdev) and samplemean<= @mean+(3*@sdev)

SELECT @sigma1 AS 'Percentage in one SD FROM mean', @sigma2 AS 'Percentage in two SD FROM mean',

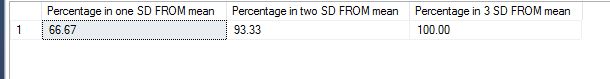

@sigma3 as 'Percentage in 3 SD FROM mean'The results I get are as below.

The results seem to be close to what is needed for a normal distribution now.

(68% of data should fall within the first standard deviation from the mean.

95% should fall within two standard deviations.

99.7% should fall within three standard deviations.)

It is almost magical how easily the rule fits. To get this to work I had to work on many different sampling sizes – to remember the rule says that it needs considerable number of samples to reflect a normal distribution. In the next post I will look into some examples of using R for demonstrating the same theorem. Thank you for reading.

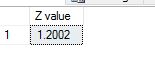

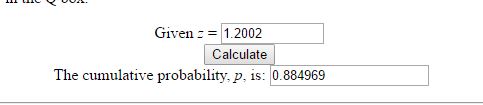

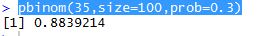

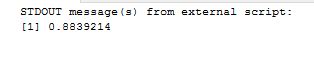

where ‘meu’ in the numerator is the mean and sigma, the denominator is the standard deviation. Let us use some tried and trusted t-sql to arrive at this value.

where ‘meu’ in the numerator is the mean and sigma, the denominator is the standard deviation. Let us use some tried and trusted t-sql to arrive at this value.